UDEME NANA JOE ATAINYANG

“For me, Village Boy is an inspiration that is sending me back to the village where I used to spend holidays with my long departed maternal Grandma.”–Udeme Nana

Every piece of literature is meant to pass a message. While literary theorists could argue that some pieces of literature are better appreciated by form and structure, rather than by content, such forms and structure would best be seen as the very import of such literary creation. What could best attain acceptance as the purpose of literature, remains the fact that literature is life. Life, in this perspective, is not the life we live. It is a creation beyond human life.

The concept of nemesis has universally become a factor that gives literature incontestable independence. Even though literature forms the basis for imitation, it does not share its boundary or restriction to the imitated. Agreed, literature could be a portrayal of human experience. Humans are mortals whose earthly sojourn are bounded by certain principles. But literature, in its idea of transcendentalism, beats the realism of the human experience. It ventures into the surreal and builds for itself the reputation of metaphysics and supernatural.

By this ascendency, the idea that literature should represent human life becomes inferior to its actual feat. Indeed, literature could tell the stories of our lives. But literature is an exceedingly overwhelming existence beyond life. Of course, while magicians try to build their profile beyond the laws of nature, literature sustains itself on the rostrum of phantasmagoria. Literature outlives life. It outlives imitation. Literature does not die after the imitated is fated to mortality. It lives centuries and aeons long after the imitated dies.

Village Boy, a literary piece in the manner of mimetic reality, has its birthday today. It is not born today because it is published today. The text is born today because the general public is officially getting to see its pages today, in the manner of public presentation. In other words, while the story in Village Boy could be centred around the author, as the protagonist, it would be found in libraries around the world thousands of years after all of us in this age stoop to mortal fate.

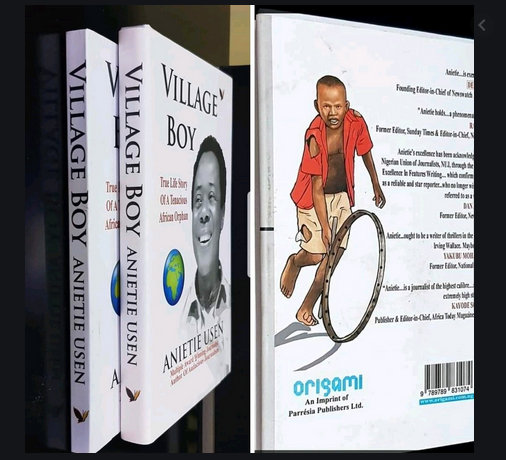

Village Boy, written by Anietie Usen, a multiple award-winning journalist and author of a 706-page book, Audacious Journalism, was published in Lagos by Parrésia Publishers Limited in 2020. It has 212 pages, including twenty (20) preliminary pages. The text consists of 23 chapters.

Wrapped in a hard ash colour paper bag, the beautiful piece of literature contained in 70-gram burn paper carries the image of the author on its front cover with an inscription, “True life story of a tenacious African Orphan”. Having a wing-flapping butterfly with black and yellow wings on the top right-hand corner, the cover page also comes with the image of a globe with the map of Africa ostensibly indicated to convey an African experience that has a universal appeal.

Belonging to the genre of literature called prose, Village Boy tells a simple story of dreams and their manifestation. It tells the story of Akan, a two-year-old orphan and only child of his father who died of wounds sustained from a fatal auto crash in Lagos. Simply put, Village Boy is a narrative revealing that though one may not be born with a silver spoon in his mouth, he can reach the peak of greatness and dine with kings and queens. The import of this story aligns with the content in the Bible as recorded in Proverbs 22:29, “Seest thou a man diligent in his business? He shall stand before kings; he shall not stand before mean men.”

Chapter One, “Footsteps of the Ghost”, narrates how Akan and his grandma mistake the sound of cockcrow for dawn and began to trek 5km from home to a stream, three villages away. The old woman, Nnenwa, who is bitten by a poisonous snake, is treated in Chapter Two, “At the Gate of Heaven”, following her herb’s prescription and she recovers. While Chapter Three, “Birthplace of Hunters” tells of grandma’s bedroom as a labour room for pregnant women and her proficiency as a traditional midwife. Chapter Four, “Castle in the Jungle” showcases the nature of the house grandma lives with her grandson, Akan and their kind of occupation, food, resting place, among others.

Chapters Five, Six and Seven offer insights into the adventurous life of African male children who go out for games and sports, especially hunting for ‘giant rats’, termites and the bull cricket which they eat as delicious meals; the fables of lizards, giant rats, the baby mosquito and others being narrated to Akan both by Grandma and Uncle Etim. This chapter captures the fact that fables served as avenues for education. Animals, insects were models which grandma and uncle Etim used to teach Akan many lessons about life.

Chapter Eight, “A Tale of Two Uncles” narrates the contrasting stories of Uncle Etim, a kind and temperate person who loves and teaches Akan, and that of a wild and uncultured Uncle Ekong who beats Akan and his mother without reservation. This philosophically depicts the two sides of life: Mr Nice guy and Mr Bad guy, Donald Trump vs Joe Biden in contemporary history!

Chapter Nine, “The Reluctant School Boy” introduces readers to the ‘pensive mindset’ of little Akan who at registration into primary school, refuses to bear the same surname as Uncle Ekong, rather choosing Godsday in the process.

Chapter 10, “A Native Doctor and a Bonesetter,” tells the painful ordeal of Akan’s friend, Zacchaeus, in the massaging hands of the bonesetter. The chapter reveals much of Grandma’s skills as a native doctor, herbalist, midwife, farmer and community leader. In Chapter 11, “A Teacher and the Hunter’s Son,” the hunter storms the school firing gunshots to abruptly end the day’s lesson, because his son, Ita, was flogged by the Compound Master, Mr Ekpo for coming to school late.

Chapter 12, “Cheat Udo No More,” captures the reason for the proliferation of churches in the African society for materialism. The account of how Pastor Atimoti lapsed into a deep sleep when he was billed to preach is very hilarious. The encounter between the prophet and MoneyHard on page 98 reveals the grandfather of the trending “StingyMen Association”. Our children should realise that these things did not start in their time. Even if your lips were bandaged with superglue, you will be forced to break in a bout of laughter while reading the encounter between MoneyHard and the Prophet.

In Chapter 13, “Motorcade in a Trance” infiltrates the subconscious of the protagonist. Here, Akan who is flogged for not supplying his “nkanya, nyang and mboi”, is intrigued by the motorcade that heralds the visit of the Premier of Eastern Nigeria, Dr Michael Okpara. The scene is quite significant because it forms the private meditation of Akan who wishes to grow into an important personality in future. A dream or was it a vision; a revelation.

Those in the ecclesiastical order would tell the difference.

Whatever its conceptualization, that stayed in the consciousness of little Akan and influenced him to perish the thoughts of low life and set his sights on loftier heights in life.

In Chapter 14, “A Journey Too Far”, Grandma and Akan boarded “The Lord is My Shepherd” lorry to Aba to visit Aunty Meme. In Chapter 15, Grandma who thinks more of her goat, farmlands, house and those who may need her service as a midwife or native doctor, cut short the holiday in two weeks and they both use the transport firm, “After God Fear Women” to return to the village. While Akan is a labourer in Chapter 16, so as to get two naira fifty kobo (N2:50) as his examination fees for his First School Leaving Certificate, Chapter 17 shows his resolve to do menial jobs in the village, instead of either being a bicycle repairer or joining Oyobio alias Holy Moses for an apprenticeship in photography.

Village life continues in Chapter 18 as Akan joins others to play Ekak, Öyö, nsa, ikara and football. In Chapter 19, his mother returns from her missionary journey and sends him as a houseboy to a pharmacy owner at Udo Street by Barracks Road, Uyo, but he returns two weeks later. Akan rejected that life as it wasn’t his calling.

His mother then took the plunge by writing letters to five of her late husband’s friends in Lagos for help. Uncle Onofiok replied with a decision to sponsor Akan throughout secondary school and he is admitted to study at Apostolic Secondary School, Ikot Oku Nsit, now in Nsit Ibom Local Government Area.

In Chapter 20, “Birth of Ambition”, Akan, who nursed the ambition to become a prefect in his school, walked the streets to sell bread and kerosine in Calabar when he visited his mother on holidays. In the process, he discovered the Library where he spent at least a day every week, reading a lot of books which set him apart from his peers. While Akan in Chapter 21 is being announced as the Senior School prefect, he, in Chapter 22, becomes a graduate of Political Science from the University of Calabar and now meets who-is-who in politics, leadership, presidents, governors and travels to anywhere in the world. Chapter 23 opens a thinking mind to the realm of philosophy as the author asserts that “being raised in poverty is an advantage and not a disadvantage.” This is a message of inspiration.

The thesis of the whole story is contained in the second penultimate paragraph of Chapter 22. The paragraph is woven into two interdependent topic sentences, flowing from the last line of page 188 to page 189. The thesis reads:

“Now, if there is anything Akan is proud of, it is the fact that he was and remains the village boy. Next to that is the knowledge that Grandma and Mamma’s God is true and does raise people from nothing to something, from nowhere to somewhere, from rags to riches, from zero to hero, from grass to grace, from victims to victors, from obstacles to miracles, from trials to triumphs, from poverty to prosperity and from the manger to the mansion.”

The class of prose fiction known as bildungsromans, Village Boy is a story of the author told with the finesse of a master narrator. The book is a chronicle of his life’s journey from childhood, youthful age to adulthood. It is a story of tenacity. It is a story of bravery; it is a story of determination and hope which ends in fame. Even though the author craftily disengages himself from the whole narrative by not using real names of concerned persons, including his, most especially by employing the third person point of view, his true confession at the acknowledgement page betrays his craft. Accordingly, the first statement in his acknowledgement, an independent clause, “This book is a product of my real experience…”, seals the deal.

Village Boy is a product of deep thinking, the reason the author is able to produce a perfect portrait with words. The title, Village Boy is incontestible because the novelist has proven beyond a reasonable doubt that such is appropriate. Out of the 23 chapters of the book, just one of them, Chapter 22, talks of the protagonist’s exploits as an adult. It is this chapter that gives currency to personal development, rise to stardom and the multiple achievements attained by the hero, Akan. This is a clear contrast to the fated rustic life entirely lived in the village throughout the whole plot. The previous chapters narrate the harsh realities of his childhood, showing his mental bravery in surmounting his multiple trials and temptations. Even his short holidays in Calabar, as captured in Chapter 21, is so short as due attention is deliberately denied the city life. This initiative helps to reinforce the idea of rural life intended by the author.

In addition to this, the traditional African objects, ideas, plants and animals flooding the pages of the text, make for the enrichment of the local colour. Examples are objects like “nkanya, mfa, ayang, nyang” p.102 and “Eben” (African pear) p.104. Others are “ikprekata” p.21, “ayod” (giant rat) p.35, “akpaisong” (ant) p.26, “ndube” (termites) p.42 and “idiang” (cricket) p.43. There are comic reliefs in the course of the narrative. The novelist intelligently adopts this technique to suppress the gloomy tension running through the tragic comedy. Uncle Etim teaches Akan how to pronounce certain English words, but the boy cannot help but commit blunders. For the word “clock” he calls “crock” and for the word “America”, he calls “Amedika” p.52. To crown it all, women flooding ‘Grandma’s maternity home’ would chant prayers in native Ibibio language thus: ” Sikofa, Sikofa, Sop dii, Sop dii, Nyom ndikut fi mfin emi…” p.19, meaning “Jehovah Jehovah, Come down quickly, Come quickly, I want to see you today.”

Told in heightened suspense, the use of dreams or trance as foreshadowing, as well as flashback enliven the storyline. Metaphors and similes also characterize the narrative style. An example is found in the statement, “For Akan, it was as scary as drowning at night in the deep blue sea”, p.6. Repetitions are also his major narrative techniques. The song of bravery sung by women during child delivery and others, keep the prose at its pace. “You will tease me in futility till daybreak”, p.21. “The village boy in a village school is a village student”, p.174. The author even uses a restricted jargon, “John Thomases”, p.156 to refer to the male sex organ.

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this story is the delineation of each of the chapters. The stylistic feature of ascribing all the chapters their independent titles generates curiosity. Chapter titles like “Footsteps of the Ghost”, “Birthplace of Hunters”, “Castle in the Jungle”, “Barbecue of Termites”, “Vernacular of Lizards”, “Motorcade in a Trance”, “The Birth of Ambition” and “From Village to Villa” give the work the desired poetic flavour. In writing the Foreward to the novel, a Professor of General Stylistics & Literary Criticism, Joseph Akawu Ushie, submits that the “chapter titles and the choice of wordings are served deliberately, as appetizers for the buffet within.”

The carefully read and blended text, however, escapes the eagle eyes of the editors, leaving traces of typographical errors in the beautiful book. For instance, the word “necromancers” is spelt “nicromancer” on page 6. Other examples are the use of the noun “proof” p.80, instead of the verb “prove”; “Sunlight soup” for “Sunlight soap”, as well as “Key soup” for “Key soap” p.130. The object, “ayang” is misspelt as “anyang” p.102. Again, the translation from Ibibio to English, of prayers by village women in ‘Grandma’s Maternity Ward’, originally written in the first person singular pronoun, “nyom ndikut fi mfin emi” p.19, is altered from the first person singular pronoun, “nyom….” – “I want….” to the first person plural pronoun, “We want….”

On page 124, the word should be oversped and not overspeeded and on page 125 ,”THE LORD IS MY SHEPHERD was lying down is not correct usage.It should read : THE LORD IS MY SHEPHERD lay overturned . Still, on that page , the printer’s devil struck by presenting the word dilapidated as “dilapidated” !

The printer’s devil should realise that this “Village Boy” is way above those common errors in Queens English or is it that the “devil” is trying to force our Village Boy back to his days with Uncle Etim?

With Village Boy, Anietie Usen is once again announcing his existence on the planet. After launching his Audacious Journalism in 2018, it seems Mr Usen is practically aligning with the idea that a child can be the father of a man. He is undoubtedly propounding a new theory that a man can exist as an adult before he becomes a child. This reminds me of our Lord Jesus Christ who actually existed as an adult, in Heaven, before becoming a child in the womb of Virgin Mary. Usen’s Audacious Journalism having been a bulk record of his career exploits as an international citizen at adult life, birthing earlier than the present, the birth of Village Boy which deals with his childhood, confirms the assertion.

The subject in Village Boy is interdisciplinary as it covers geography, history, culture, religion, education, career, leadership, transportation, and many others. It is both a story worth writing and a story worth reading. It appeals to the mind, intellect and emotion. It remains an archetype of African literature. As Prof. Joseph Ushie would rightly admit, the book should attract the attention of curriculum designers for secondary and tertiary institutions and interest scriptwriters and actors of African movies, due largely to its universal application.

For me, Village Boy is an inspiration that is sending me back to the village where I used to spend holidays with my long departed maternal Grandma. The bubbling muse can sustain a recollection of the memories of the rustic life familiar to African communal existence. The book is like a Bible with a soothing balm to wounded minds.